Geoffrey Penrose Dickinson 19/07/1916 - 18/01/2005

Mary Ogilvie Carlisle ??? - 2010

Married

Published 22/01/2016

updated 07/04/2016

CHILDREN

1. Virginia Anne Ogilvie 1946 - 1998

2. Nicholas Arthur Dickinson 1949 -

Articles and links

1. Transcript of Obituary of Geoffrey Penrose Dickinson Hall.

3. Adrian Michael Dickinson 1955 -

REAR-ADMIRAL GEOFFREY HALL

Master surveyor who won the DSC in a daring reconnaissance of Japanese defences and became Hydrographer of the Navy

GOEFFREY HALL was the twentieth Hydrographer of the Navy since the post was established in 1795. As such, he was the leader of an organisation which has been responsible for the navigational charting of almost the entire world. The famous Admiralty Chart in all its forms was first placed on the open market in 1823 and was thereafter used worldwide by the merchant ships of many nations.

Hall's long and varied seafaring career, which included six sea commands, began in the training cruiser ?robisher in which he attended the Silver jubilee Fleet Review of 1935 at Spithead. As a midshipman in the ancient cruiser Dragon, he helped to show the flag around South America.

On his transfer to the modern cruiser Southampton, he had his first taste of action during the politically confused Spanish Civil War, when an alarming number of contrived or accidental attacks on the shipping of other nations required protective responses and the succour of many categories of refugees fleeing from the conflict, in which Franco's insurgency was openly backed by Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy.

During sub-lieutenant professional courses at Portsmouth, Hall made up his mind to join the surveying service. After a period measuring the tides and the movement of sandbanks in the Thames Estuary in the survey vessel Franklin, he was appointed to the sloop Scarborough and helped to survey the coast of British Somaliland and the east coast of Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

At the outbreak of war in 1939, Scarborough was in Singapore where Hall, with other surveyors, manned reserve fleet minesweepers and hurriedly learnt to trade.

Relieved by RNVR officers, he was flown home and as a lieutenant in the Challenger, took part in a survey to equip the supposedly secure anchorage at Scapa Flow with controlled minefields and detector loops in order to prevent a recurrence of the disaster to the battleship Royal Oak, which had been sunk at anchor by the bold U-boat captain GŁnther Prien.

Although Challenger, as a survey vessel, was quite unsuitable as an escort, circumstances in June 1941 required her, with two corvettes, to lead a convoy to West Africa during which a troopship, the Anselm, was torpedoed. Hall graphically described this disaster: "Although brilliantly handled, the escorts saving some 1,500 of the 2,000 soldiers on board, many broke legs jumping down to Challenger's deck and many more were sucked under as Anselm sank".

Carrying more than a thousand survivors who were understandably reluctant to go below decks, Challenger's stability (she was a mere 1,140 tons displacement) was seriously affected.

Challenger went on to survey the navigability of the steamy Gambia river, which was to be used as a convoy assembly point but was at that time almost unchartered. She returned home in January 1941.

Hall had requested to transfer to general service - the mainstream Navy -and was now allowed to do so. He qualified as a navigator and was appointed to the staff of the mine-sweeping squadron, operating, often under an air treat, against submarine-laid mines around the shallower waters off Iceland in support of Murmansk convoys.

At one point, on return to Greenock, Hall was surprised when "a dark-haired pleasant-looking lieutenant called Geoffrey Lyne" introduced himself as Hall's relief - they were to do a swap. Reluctant to move, Hall was reminded that he had volunteered for "hazardous service" sometime earlier. As it happened Lyne had been in combined Operations and had been captured by the Vichy French during a beach survey for OperationTorch, the Allied landings in North Africa. Hall thus found himself training for a combined-operations pilotage party.

This was based in India and was part of an innovative and enlarging capability, aimed at surveying beaches suitable for amphibious assault. Hall's first assignment, in October 1943, was the island of Akyab off the Burmese coast, which was to be approached by motor launch and canoe, equipped with "a crate of carrier pigeons and a bottle of pills inscribed 'Instantaneous Death - to be taken with discretion'".

Creeping about in the dark, Hall's team ascertained the absence of any Japanese, and carried out their reconnaissance of the defences, establishing the beach gradients, all the while acutely conscious of the threat from landmines and sharks. For this operation, Hall was awarded the DSC.

He was subsequently awarded a mention in dispatches for a three-day operation on the northern coast of Sumatra in August 1944. For this he landed by canoe from the submarine Tudor.

On return to UK in early 1945, he was appointed to command the frigate Bigbury Bay, then under construction at Aberdeen. He also took the opportunity to marry his fiancťe, Mary Carlisle, then a WRNS officer at Portland. While working up at Tobermory under the eagle eye of the formidable Vice-Admiral Sir Gilbert "Monkey" Stephenson, Commodore of the Western Isles - and an important contributor to winning the Battle of the Atlantic - Hall heard of the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima.

Bigbury Bay-sailed to Hong Kong and was very active in the chaotic aftermath of the Pacific war. Her duties were anti-piracy patrolling and the recovery of internees from Japanese camps. After an enjoyable visit to Australia, Hall was ordered to Tokyo under American command, there to embark Japanese servicemen accused of war crimes - many of a horrific nature - and take them to Hong Kong for trial.

After two years in command, Hall returned home by troopship and applied to re-join the naval hydrographic service. After a tour in the comparatively lowly position of second-in-command of the survey ship Seagull, working in the Bristol Channel and off the West Coast of Scotland, Hall was offered the post of second-in-command of the Royal New Zealand Navy's only survey ship, the Lachlan. Accompanied by his family, this was a happy and adventurous two years.

On his return home in 1952, Hall was appointed captain, successively, of the survey vessels Franklin and Scott, conducting surveys of the Thames Estuary and the northern Irish loughs. Promoted to commander, he was appointed superintendent of the oceanographical branch, dealing with, among other things, the amassing of data concerning the temperature structure of the sea around the world - critical to the acoustic detection of submarines. He was amused by his ex-officio membership of the British national committee on the Nomenclature of Ocean Bottom Features - knows as the NOB committee.

Command of the survey ship Owen (originally built as a frigate) followed, with surveys of the East and West coasts of Africa, in the Seychelles and off Gibraltar. In 1958 Hall worked in the Admiralty, managing the charts needed by the naval staff, and working with Nato on the standardisation of radio aids and similar matters.

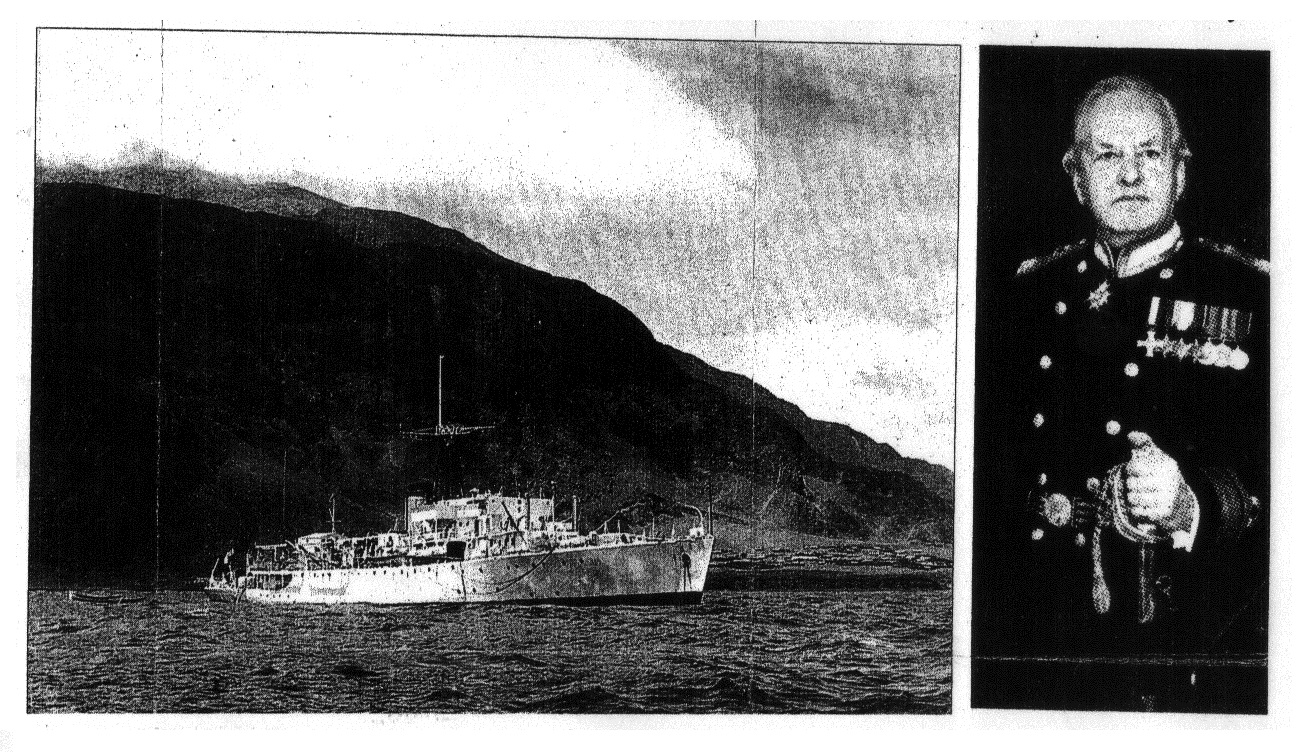

A second tour in command of Owen concerned oceanographic surveys of the mid-Atlantic deeps; the recovery of sediment cores; visits to St Paul's Rocks and Tristan da Cunha; and intricate and sometimes - because of the violent weather and the necessary use of the ship's boats - hair-raising surveys of South Georgia.

Owen was then employed in the Indian Ocean as part of the 1962 International Geophysical Year, completing an epic voyage that included some 53,000 miles of new oceanic soundings.

For his work in furthering oceanographic exploration Hall was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's Cuthbert Peek grant. Promoted to captain, he went to Whitehall as Assistant Hydrographer.

Then, in 1965, he was given command of the new survey ship Hecla which was mainly employed on North Atlantic surveys with their new operational focus on the position of sea-bottom contours in support of Britain's Polaris submarine force.

He was promoted rear-admiral in 1971 and appointed Hydrographer of the Navy that year. During his time in post he fought hard, and with political acumen, for the preservation of the Royal Navy's surveying capability in the desperate economic climate of those days.

In September 1975 he took the unusual step for a serving office of airing his concerns about the effects of starvation of funds for surveying on the nation's mercantile life in the strenuously argued letter to The Times, pointing out that "the work of the Hydrographic Service represents the greatest single contribution which the Royal Navy makes to the civil community in peach time".

Such temerity caused consternation in the Admiralty, and incurred "their Lordships' displeasure" - an official slap on the wrist for the Navy's chief hydrographer.

He was appointed CB in 1973 and was president of the Hydrographic Society from 1975, in which year he retired from the Navy and settled in Lincolnshire. He was a Deputy-Lieutenant of the county, a supporter of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England and of Lincoln Cathedral. His memoir, Sailor's Luck, appeared in 1999.

He is survived by huis wife Mary and their two sons, their daughter Virginia having died in 1998.

Rear-Admiral Geoffrey Hall, CB, DSC, Hydrographer of the Navy 1971-75, was born on July 19, 1916. He died on January 18, 2005, aged 88.

Hall: during a nine-month oceanographic commission in command of the survey ship Owen, seen here off Tristan da Cunha in 1961, he surveyed South Georgia and the mid-Atlantic deeps.